Astounding cyberheists and politically motivated cyberattacks have

one thing in common: They invariably begin with simple trickery.

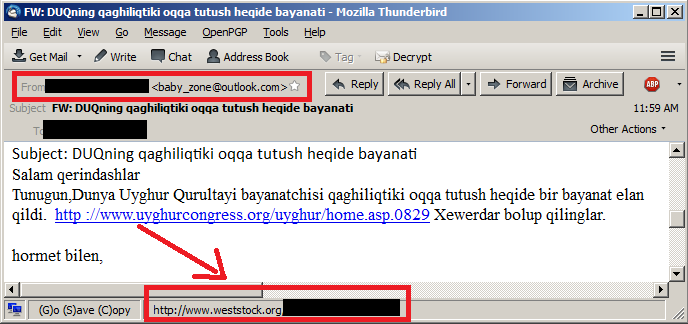

Top-tier cybergangs and hacking collectives, such as Anonymous and the Syrian Electronic Army, are taking full advantage of search engines and social websites to compile rich profiles on individuals. This information is then used to target individuals to receive an e-mail ruse known as a spear phishing attack. The e-mail carries a viral PDF attachment or Web link.

The bad guys are pulling out all the stops to profile executives and their charges, then crafting an e-mail carrying a viral PDF attachment or Web link from the boss to the subordinate. The goal: to trick the subordinate into following orders to click on the viral payload.

"A great deal of time and money is spent crafting these attacks," says Nicholas Percoco, senior vice president at data security company Trustwave. "The attackers know business relationships and understand how the person they are impersonating constructs his messages."

Most often the bad guys seek the user name and password of an employee who they believe has privileged access to sensitive databases and internal applications.

"If you look through the history of recent breaches, every one of them has a privileged connection," says John Worrall, chief marketing officer at security firm CyberArk.

The empowerment gained from possessing just the right logon is limited only by the attackers' imagination.

The pro-Syrian hackers who cut off The New York Times' website for 20 hours last week, for instance, lured a distributor working for Melbourne IT, a registrar that helps direct Web traffic, into divulging his user name and password. With that distributor's credentials, the attackers were able to redirect traffic intended for nytimes.com to a website they controlled.

The FBI earlier this year put a crimp in a crime syndicate that by then had pilfered $45 million from ATMs, using data stolen from a major payment processing company. The thieves likely got inside the payment processor's network by spear phishing an employee. Not only did that enable them to steal payment card account numbers and PINs, they also boosted the ATM withdrawal limits on hundreds of accounts for which they had stolen card numbers.

The account numbers were then embedded on blank mag stripe cards and distributed with the accompanying PINs to an army of recruits, who then hit the streets to make large ATM withdrawals. The FBI caught a handful of these street operatives, but the masterminds are still at large.

In another inventive heist, a crime ring launched denial-of-service attacks against several banks' websites. While tech staff labored to restore service, the bad guys used a bank employee's privileged logon to access a master payment switch for issuing wire transfers.

Thus, a successful spear phishing campaign enabled the thieves to flick a switch to wire funds into accounts they controlled on a mass scale, says Avivah Litan, Gartner banking security analyst. "Considerable financial damage has resulted from these attacks," says Litan.

Last fall the FBI issued an alert about criminals targeting bank employees, in particular, for spear phishing attacks. However, politically motivated hacking groups have begun spear phishing employees who are once or twice removed from the targeted website, as The New York Times hack showed.

The lesson: We all need to to stay alert.

"The entire attack sequence often begins with a very legitimate looking e-mail with a juicy story prompting the victim's computer to become infected," says Percoco. "Companies should educate their employees that these type of attacks are very real and to be vigilant all day, every day when using e-mail, social networks and the Web."

Top-tier cybergangs and hacking collectives, such as Anonymous and the Syrian Electronic Army, are taking full advantage of search engines and social websites to compile rich profiles on individuals. This information is then used to target individuals to receive an e-mail ruse known as a spear phishing attack. The e-mail carries a viral PDF attachment or Web link.

The bad guys are pulling out all the stops to profile executives and their charges, then crafting an e-mail carrying a viral PDF attachment or Web link from the boss to the subordinate. The goal: to trick the subordinate into following orders to click on the viral payload.

"A great deal of time and money is spent crafting these attacks," says Nicholas Percoco, senior vice president at data security company Trustwave. "The attackers know business relationships and understand how the person they are impersonating constructs his messages."

Most often the bad guys seek the user name and password of an employee who they believe has privileged access to sensitive databases and internal applications.

"If you look through the history of recent breaches, every one of them has a privileged connection," says John Worrall, chief marketing officer at security firm CyberArk.

The empowerment gained from possessing just the right logon is limited only by the attackers' imagination.

The pro-Syrian hackers who cut off The New York Times' website for 20 hours last week, for instance, lured a distributor working for Melbourne IT, a registrar that helps direct Web traffic, into divulging his user name and password. With that distributor's credentials, the attackers were able to redirect traffic intended for nytimes.com to a website they controlled.

The FBI earlier this year put a crimp in a crime syndicate that by then had pilfered $45 million from ATMs, using data stolen from a major payment processing company. The thieves likely got inside the payment processor's network by spear phishing an employee. Not only did that enable them to steal payment card account numbers and PINs, they also boosted the ATM withdrawal limits on hundreds of accounts for which they had stolen card numbers.

The account numbers were then embedded on blank mag stripe cards and distributed with the accompanying PINs to an army of recruits, who then hit the streets to make large ATM withdrawals. The FBI caught a handful of these street operatives, but the masterminds are still at large.

In another inventive heist, a crime ring launched denial-of-service attacks against several banks' websites. While tech staff labored to restore service, the bad guys used a bank employee's privileged logon to access a master payment switch for issuing wire transfers.

Thus, a successful spear phishing campaign enabled the thieves to flick a switch to wire funds into accounts they controlled on a mass scale, says Avivah Litan, Gartner banking security analyst. "Considerable financial damage has resulted from these attacks," says Litan.

Last fall the FBI issued an alert about criminals targeting bank employees, in particular, for spear phishing attacks. However, politically motivated hacking groups have begun spear phishing employees who are once or twice removed from the targeted website, as The New York Times hack showed.

The lesson: We all need to to stay alert.

"The entire attack sequence often begins with a very legitimate looking e-mail with a juicy story prompting the victim's computer to become infected," says Percoco. "Companies should educate their employees that these type of attacks are very real and to be vigilant all day, every day when using e-mail, social networks and the Web."